How to Read Scottish Snare Drum Notation

PROLOGUE to Examples of Snare Drum Annotation:

I have studied military snare drum manuals published during the 18 and xix centuries. They provide insights into the beats drummer'southward played and the blazon of drum didactics available 100 or more years agone. They have their own personalities and the diaries written with quill pens, books printed with crude type, hand made newspaper, colorful, antiquated language and interesting notation provide glimpses into the life and times of their authors.

As I turned pages, I became fascinated with their unique and sometimes indecipherable notations. Had these been invented to assistance drummer boys learning the military campsite duties, boys who were often unable to read music, or had the teachers, grappling with the intricacies of a drum beat, been forced to invent their own notations, or both? But those theories didn't make consummate sense.

For example, music annotation had get highly evolved and standardizeds during the Baroque era (ca. 1600-1750), well befor the first drum manual was published in America in 1810. An extensive prepare of symbols, particularly for keyboard and string music, was developed for embellishments ranging from unmarried grace notes to trills and complex ornaments. Thomas Arne (1710-78) wrote in traditional annotation, eight and v stroke snare drum rolls for March with a side drum in his Masque Alfred (1740).

Then, why did teachers of the drum develope their own unique notation and sometimes classification, while all the music surounding them was using a note familiar today. I believe the answer is rather mundane. The authors wanted to sell books. Information technology is interesting to annotation how oftentimes the words best, accurate, most, easiest, true, approved, consummate, etc. announced on their forepart pages immediately later the title.

The war for independence had just ended and the tradition of local militiamen was notwithstanding very strong. In New England where all of these books were written, every village, village, and town maintained an armed militia and at least one fifer and drummer. This area of the U.s.a. was still sparsely settled particularly outside a big town such as Boston. Contest amongst teachers and teaching methods and rivalries between militias and their fifers and drummers must have existed, as they proceed to do.

Today, Much attempt has been expended by teachers and instrument manufacturers in attempts to standardize sound, methods and nomenclature. In Examples of Snare Drum Annotation one will meet not so much an evolution of the drummers craft as his independent spirit. As the reader will discover at the finish of Function three, in that location are drummers still marching to a different notation.

Role 1:

Until the early on twentieth century, education books for snare drummers were written to conform with military protocol.1 These books contained names for drum strokes, signals for army camp duty and field maneuvers, exercises or 'rudiments'2, and often, appropriate tunes for fife, the musical instrument most commonly paired with the field snare or side drum. They did not tell drummers how the drum was played,iii

Creating symbols for the snare drum strokes, signals and exercises, and staves upon which to put them, has occupied players and teachers of military drumming for at least 350 years. The examples of drum note which follow, are arranged as closely as possible in chronological order and stand for all extant drum manuals or fragments thereof in my possession from the period of fourth dimension covered

1555? The first mention of military drum signals in English history, date from the reign of Queen Mary (1553-58). They practical to foot soldiers and were titled March, Alarm, Approach, Assault, Battle, Retreat and Skirmish. However, these seven signals survive as names merely, no music notation for them is known to exist.4

1589. The earliest extant music notation for military drum is in Orchesography, a treatise on the honourable practice of dancing by Thoinot Arbeau, published past Jehan des Preyz, Langres, France.five

1589-Orchesography,Thoinot Arbeau, Langres France.

Arbeau'due south annotation is easily understood today if one reduces each note by one-half, i.e., a half note (minum) to a quarter note, a quarter to an eighth, etc. There are no grace notes or rolls in Orchesography. The right manus plays the starting time note of each group and both hands together play the last note. The correct hand stroke coincides with the left foot, and the fifth note-hands together-coincides with the right foot, thus completing 1 stride. This sequence of right paw-left foot, left hand-correct foot, "keeps the player in rest" while marching.6 Some scholars believe the 16th c. minum was a relatively quick shell much similar the quarter note today; perhaps 115 beats per minute"

1627. Bonaventura Pistofilo's, Torneo (Bologna, Italy,), a book of illustrations instructing Cavaliere (Knights or soldiers) in postures for weapon'southward drill, vii contains, according to James Blades (1901-99), the kickoff drum beats actually used in a military context.viii In the example below, lines i and three show the drum beats, while lines ii and four dictate the soldier's movements in response to the drum. The notation is similar to Arbeau, merely the bar lines, typical of the age, do not mean what they hateful today.*9

1621-Torneo, Bonaventura Pistofilo.

In that location are other mysteries equally well. What is the relationship between "Primo tempo" and "Secondo Tempo"? What is the pregnant of the dots over some notes, the + ('crosses') and the numbers 1, 2, 3, four, which announced only nether the soldier's staves? These remain to be deciphered, but the onomatopoeia device, here, ta – pa, was also used in Arbeau and will be familiar to mod military machine drummers.10 So likewise is the stalk down, stem up notation which may make its outset appearance here, and probably indicates right and left easily, a device in utilise to this 24-hour interval.

1632. Charles I of England(1625-49), issued a Warrant directing the restoration of the English March to its original rhythm as information technology had suffered from improper interpretation. Copies of the march and warrant have appeared in diverse texts. The original has not been found.

1632-Warrant, English March.

At starting time glance, the deciphering of this beat seems to be at our fingertips: the notation in Arbeau and Pistofilo are similar, just how this march was played, has been argued since its actual audio faded from memory.11 Annotation the use of both single and double bar lines, fermatas, and the onomatopoeia, here pou and tou, with a terminal poung.12 The capital R, appears with intriguing regularity and may indicate a roll or a ruff; maybe a key to deciphering the March.

1634. Later these tantalizing examples of almost decipherable drum notation,two unique and aggravatingly obscure manuscripts announced. The first is a version of The English March shown in the Warrant above and published by Thomas Fisher in Warlike Directions or the Soldiers Practice.13

1644-Warlike Directions, Thomas Fisher.

1= Left Manus, I= Right Hand, r= Total Ruff, 2= 1/two Ruff, Ir= Stroke and Ruff, r2= A Ruff and a half joined together. (6 Rudimenss in this chirapsia.)

The Preparation. which precedes the drum beat is, in Charles' Warrant,The Voluntary Before the March

In the judgement below the pulsate beating, Fisher says, "I have insisted somewhat long in the office of the drummer, and so that I find a not bad deficit in that place, and would wish a more general reformation." Fisher is petitioning Rex Charles I for a job as drum instructor throughout the kingdom, and if the credentials he gives for himself in his book's preface are believable, he may well have been qualified.

1650-xc. So, this curious certificate. Discovered glued to the inside of a book in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, England, it is referred to as the Douce (pronounced Dowse) Document subsequently the book's original owner. Shown beneath is one page of the document titled "The Grounds of Chirapsia Ye Pulsate". Under this title, bundled from left to correct, are 11 symbols or pictographs representing drum strokes or rudiments.

1650-xc (ca.)-Douce, Grounds for Beating Ye Drum.

The interpretations for these symbols read as follows: "one stroke and a touch on", "Is a plain stroke", "Is four strokes beginning easy and ending hard", "Is a half ruffe beginning loud and catastrophe loud", "Is a whole ruffe which is 5 strokes ending loud", "Is a ruffe and half which is 8 strokes", , "Is a stroke with both sticks together", "Is a stroke with both sticks and a touch on", "Is rolling ii sticks with one manus and two strokes with ye other", "Is continual rolling", "Is a bang by ye hoop" (a Pointing, Poung, pong or poing stroke? There is a like education in Levi Lovering's 1818 book,folio 9.Meet my posting "What was a Poing Stroke?")

1777 . Reveille from Trommel Spielett, George 50. Winters,(Berlin); according to the late James Blades,the earliest military pulsate manual in being. The up slanting being this on all the roles betoken crescendos. (A combination of upwards and downward slanting beams announced on other pages in the manual.) The beating below is identical to the Reveille in utilize today in the Swedish and Dutch armies. (see Part II)

1777-George Fifty. Winters, Berlin.

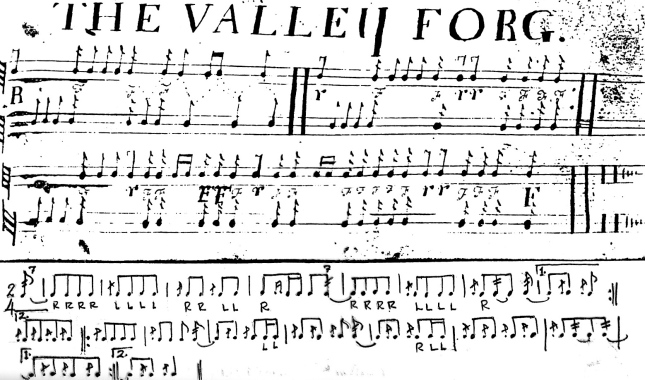

1778. The Valley Forg (sic)drum beating beneath, is from A Revolutionary War Drummers Volume, a possession of the Massachusetts historical Lodge. It's twenty nine pages were written entirely with a quill pen, and comprise much to recommend them to drummers. On his opening pages the bearding writer lists xx exercises (rudiments). He begins with what he terms "The Dominion of the first ringlet or Gamut for the Drum" i.eastward. closing the long roll.Included likewise is a Twelve stroke roll.

In the example below, the very start note is an eighth note with a backward beam. This is a 7, and indicates a seven stroke role, the first six notes of which precede the downbeat, but are not shown. "The letter R signifies A roll". The two staves which separate Correct and Left hands, are, to my knowledge, the primeval extant instance of this device, a variant of the unmarried stave with up and downwards stems in The Young Drummers Assistant from the same menses.

1778(ca.) A Revolutionary War Drummer'south Book.

Above is my estimation of the Valley Forg beat. Every drum chirapsia in the volume was named for a melody it was meant to back-trail. (The Valley Forg(e) is a tricky melody.) Finding these tunes, many existing under different names,and transcribing the drum beatings into mod notation,was often a challenge, but always exciting.

1779-84. With the appearance of The Young Drummers Banana (London), illustrated below, drum notation appeared to be continuing in the mainstream of common practice, and the Thomas Fischer and Douce manuscripts appeared to have been anomalies.

1784(ca.)-Young Drummers Assistant, London.

The Immature Drummers Assistant may well be the first drum manual published in the West utilizing iii line notation; the notes on the middle line bespeak the principal beats, in this example, the end note of rolls. Stems upward indicate the Left hand, stems down, right hand.

"Mother", is the 5 stroke roll.(See Ashworth, Part II) This volume contains 12 "Marks" (rudiments), but the 5 stroke roll is not among them. Interestingly, "Roll Continued" is listed recalling the "Roll Standing" in the Douce Document from approximately 100 years earlier. Too included is a "Pointing Stroke" Which cannot help but remind one of the "Poing Stroke".

ca.1780-90. This Volume titled Scotch (sic) Duty Beatings is office of the Thomas Shaw–Hellier collection devoted to mid to late 18th-century music manuscripts in possession of the Music Library, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, England. The staff of the Shaw–Hellier collection has not been able to date this manuscript, only agreed with me that based on its similarity to The Immature Drummers Assistant higher up, it probably dates from the same decades, The Scotch Duty Beatings's staves are printed, merely the note is by hand and made with quill pen. I have chosen to reproduce a like section of Mother and three Camps Reveille from both books. The book contains 12 rudiments including a Six stroke rol50.

ca1780-Scotch (sic) Duty Beatings

1788. Dice Erste Tagwacht, (Reveille.) The text reads: "The First Morning Call. To every measure of this morning phone call belongs a footstep. One will e'er beat the offset and 2d part twice." (repeat both parts always.)

1788-Swiss notation, Reveille.

A totally phonetic approach to teaching drummers. This Tagwacht drum chirapsia "from the Berner Ordommanx1788. Probable even earlier, it appears as the identical French drum call, 'Premier Reveille' with the pretty melody, 'Goddess Diana at the Break of Day.' The oldest known morning call".14

1797. Below is a reproduction of one page from Benjamin Clark'south Drum Volume Titled Rules for the Pulsate. The note is like to The Young Drummers Assistant and the Scotch Duty aboveexcept for the direction of the annotation stems, and lists rolls of varying lengths – the long ringlet, x, nine, vii, five, and 3 stroke rolls, likewise every bit drags and 'ruffe'. Clark's volume was discovered in 1974 by Kate Van Winkle Kellerand subsequentlySusan Cifaldi nerveless and transcribed the fife tunes to match the books drum beatings transcribed into mod note by Bob Castillo.xv

1797-Benjamin Clark drum book.

Clark's book contains nine exercises (rudiments) including a Iii stroke roll..

Footnotes to Part 1:

ane. In the tardily nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two men wrote instruction books for percussion instruments which deviated from the war machine norm. Harry A. Bower, who played in the Boston Symphony(1904-07), was first in 1899 with his Imperial Method for the Drums, Timpani, Bells Etc.. The John Church building Co., Philadelphia, PA., and followed in1911 with his System for Drums, Bells, Xylophone and Timpani., Carl Fischer, Due north.Y.

Carl E. Gardner was side by side in 1919 with his Modern Method for the Drums, Cymbals and Accessories, Carl Fischer, N.Y. Gardner had besides played with the B.S.O. and, at the fourth dimension he wrote his books, was Supervisor of Bands and Orchestras in the Boston Public School Arrangement.

Though the books of both men contained some of the essential rudiments–flams, ruffs, and brusk rolls– Bower and Gardner wrote primarily to railroad train percussionists for symphony orchestra, Vaudeville and theatre orchestra snare, timpani and mallet playing.

2. The word 'Rudiments' showtime appears in impress on folio three of A New Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating by Charles Stewart Ashworth, published in Boston, Massachusetts in 1812. A complete listing of exercises or rudiments shown in each book volition be attached to the end of Function Ii. (Also, run across my commodity, A Brief Note on Drum Rudiments posted on this blog.)

3. In his Imperial Method for the Pulsate (1899), Harry A. Bower included iii very elementary line drawings intended to bear witness the right and left hand grip and the proper bending for setting a concert snare drum. In his System for Drums, Bells, Xylophone and Timpani (1911), Bower used photographs to more clearly show the hand, arm and playing positions for the snare drum.

4. Grosse, War machine Antiquities, 1801, in Henry George Farmer: The Rise and Evolution of Military Music, 1912-1970. These seven signals (commands) practice, nonetheless, propose a rather sophisticated drum technique, equally each betoken would have been distinctly dissimilar, one from the other, in order to impress itself upon men engaged or about to exist engaged in the stress and distractions of battle. When encamped, a 16th c. army may well have used boosted signals such as Reveille, Assembly and Tattoo, which, in 1 course or another, were common camp duty signals of the 18th and 19th c. It may reasonably be assumed that drummers of the 16th c. had a required repertoire of ten or more distinctive drum beats.

5. Thoinot Arbeau: Orchesography, Dover Publcations, New York., soft comprehend. Orchesography is in the grade of a dialogue between its author and his student Capriol, The first chapter explains the correlation between drum beats and moving soldiers together in time, calculating altitude and time of travel. Arbeau illustrates how seventy-half dozen variations of five consecutive minims tin can be created by gradually substituting crochets and quavers for the first four minims.

6. This right, left correlation persists today, even in some non-armed services snare drum solos. The right hand, ordinarily the strongest, plays the offset shell of each mensurate, thus helping to clarify a beat out's tempo and grade. Historically, left handedness was considered to exist evil, unnatural or simply undesirable. Even today, some left handed immature people are forced to use their right hand, specially for writing. Left handed drummers take always been required to begin with, or change to, a correct mitt grip in order to adapt to either the uniform appearance of a war machine drum line, or with pulsate methods and solos based on a correct manus pb. The matched grip, then prevalent today, has not entirely done away with left handed issues, as the music military drummers play is written, intentionally or not, from a right hand perspective.

7. Besides emphasizing martial prowess, many of the postures are balletic; befitting the age of Chivalry which empathized grace, refinement, award and noble gestures.

8. James Blades and Jeremy Montague: Early Percussion Instruments from the Middle Ages to the Baroque, (page 11),Oxford Academy Press, 1976.

9. Understanding the precise role of bar lines during the 16th c, is problematic. They were non always employed, and when used, seem to have served unlike purposes depending on the composer. In the 15th century, vertical lines were used to dissever the staff into sections. These lines did not initially divide the music into measures of equal length every bit well-nigh music then featured fewer regular rhythmic patterns then in afterward periods. The use of regular measures became commonplace by the end of the 17th century. In Orchesography, Arbeau does not use bar lines in his pulsate beats, possibly considering of their curt, uniform length, but he does employ them occasionally and always in his melodic examples.

10. For example: Paradiddle, ratamacue, ruff and flam.

xi. See Maurice Byrne: The English March and Early on Drum Annotation, Mr. Byrne spent a good bargain of his life comparing and analyzing the English language March as it appears in the iv known copies of the Charles I Warrant, with the notation in the Fisher and Douce manuscripts and their subsequent reflections in The Young Drummer's Assistant and Samuel Potter (1815, see office Ii).

Mr. Byrne's newspaper is fascinating, informative and a joy to read. However, if one thinks a last solution to the enigma of the English March awaits, a sentence in Byrne's second paragraph will give pause. "All of these notations are incomplete,* simply by analyzing their basic rhythm it is possible to interpret the significance of the intermission sign which they use and then that the march tin exist written down in modern note". Dr. Harrison Pawley of Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, told me he knew without doubt how this English March was played, but did not volunteer his solution. (*emphasis mine)

12. This appears to exist the Pong or Poing stroke of the tardily 18th century. (Run into my posting What Was a Poing Stroke?)

13. I am grateful to Graeme Thew, Principal Percussionist, Grenadier Guards Ring, for providing me with copies in readable script of the Thomas Fisher and Douce manuscripts.

14. I am indebted to the eminent Swiss percussionist Fritz Hauser for his translation of Tagwatch and other texts from Trommeln Und Pfeifen In Basel, CD 181996 BREO, a 3 Meaty Disc history of Swiss drumming.

15. In a phone conversation Ms Cifaldi told me she had found very faint watermarks on some of the pages of Clark's book. These watermarks belong to a printer in Boston who operated between the years 1800 and 1810. All the same I have decided to place this manuscript in the 18 c. because Clark, though maybe writing his book at a later date, had been a drummer in the War for Independence (1775–83) and had himself dated the volume.

Benjamin Clark'due south Drum Book 1797, Containing 36 Drum Beatings from the year 1797 and 46 Fife Tunes from the same time period With appropriate historical notes provided by the editors. Pulsate Beatings rendered into modern notation by Bob Castillo, Fife Tunes collected and transcribed by Susan Cifaldi, copyright 1989 Susan 50. Cifaldi. This book may be purchased from Mr. Leo Brennan: colonialsutler@comcast.net> Price, $15.00 plus postage.

Source: https://robinengelman.com/2010/06/26/examples-of-snare-drum-notation-part-1-1589-1788/

0 Response to "How to Read Scottish Snare Drum Notation"

Postar um comentário